As I have noted on this site, the SEC has in recent months filed SPAC-related enforcement actions, including the action filed in July 2021 against Stable Road Acquisition Corporation (discussed here), and the Y, 2021 action filed against Nikola Motors founder Chad Milton (discussed here). These matters were not, however, the first SPAC-related SEC enforcement actions; there have been others previously, including the September 2020 SPAC-related enforcement action against music streaming company Akazoo, S.A. In something of a milestone regarding SPAC-related actions, on October 27, 2021, the SEC announced that it had reached a settlement of the Akazoo enforcement action. The SEC’s October 27, 2021 press release about the settlement can be found here. The October 27, 2021 Agreed Final Judgment in the Enforcement Action can be found here.

As I have noted on this site, the SEC has in recent months filed SPAC-related enforcement actions, including the action filed in July 2021 against Stable Road Acquisition Corporation (discussed here), and the Y, 2021 action filed against Nikola Motors founder Chad Milton (discussed here). These matters were not, however, the first SPAC-related SEC enforcement actions; there have been others previously, including the September 2020 SPAC-related enforcement action against music streaming company Akazoo, S.A. In something of a milestone regarding SPAC-related actions, on October 27, 2021, the SEC announced that it had reached a settlement of the Akazoo enforcement action. The SEC’s October 27, 2021 press release about the settlement can be found here. The October 27, 2021 Agreed Final Judgment in the Enforcement Action can be found here.

Background

According to the SEC’s complaint against Akazoo (a copy of which can be found here), Akazoo claimed to be an emerging-markets-focused music streaming service with nearly 40 million registered users, nearly five million subscribers, and over $120 million in annual revenue. In actuality, the SEC alleged, the company had no paying users and negligible revenues. Akazoo, the complaint alleged, leveraged these misrepresentations to enter into a September 2019 business combination with the special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), Modern Media Acquisition Corporation (MMAC). (Further background regarding the SPAC and the business combination are further detailed in the separate private securities class action lawsuit that investors filed against Akazoo and others in April 2020, as discussed here.)

As a result of the business combination, Akazoo’s shares became listed on Nasdaq. The SEC alleged that after the shares began publicly trading, Akazoo “proceeded to defraud” investors by misrepresenting that it had earned tens of millions of dollars in revenue during 2019 and increased the number of subscribers 28%. In reality, the SEC alleged, the company in fact had limited operations and no subscribers, “all while depleting more than $20 million in investor funds.”

According to its recent press release describing the settlement, the SEC filed an “emergency action” against Akazoo in order to “preserve the company’s remaining $31.5 million in cash and other assets.” In April 2021, without admitting or denying the SEC’s allegations, Akazoo agreed to a bifurcated judgment that permanently enjoined the company from violating the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws.

The SEC enforcement action settlement announced on October 27, 2021 fully resolves the SEC litigation by ordering Akazoo to pay $38.8 million in disgorgement, an amount, the press release states, “that will be deemed satisfied by the company’s payment of $35 million to investors and victims of settlements in connection with several private class action lawsuits.” The separate April 2021 settlement of the private securities class action litigation is described in detail in a prior post on this site, here.

Discussion

This sequence of events, including the settlements, along with the other SPAC-related enforcement actions show the extent of the SEC’s interest in monitoring SPAC-related transactions and market activities. Indeed, the SEC’s October 27 press release announcing the Akazoo settlement includes a statement from an SEC official as saying that “The SEC is intently focused on SPAC merger transactions, and we will continue to hold wrongdoers in this space accountable.”

For insurance and legal practitioners active in the SPAC arena, both halves of this SEC’s official’s statement are noteworthy; first, it represents a declaration that the agency is not just watching SPAC activity but is in fact “intently focused” on it; and, second, it represents a further declaration that the agency is going to continue to pursue alleged misconduct in SPAC-related activities.

The SEC settlement itself is a little bit unusual from my perspective. The enforcement action settlement is really just a piggyback on the separate private securities class action lawsuit settlement. This kind of an arrangement may not be unusual, but off the top of my head I don’t recall seeing a prior instance where the SEC so clearly accepted a private securities litigation settlement as sufficient to fulfill the agency’s objectives in filing its own enforcement action.

The SEC official’s statement in the press release includes a comment with respect to the settlement of the Akazoo action to the effect that “One goal in filing this emergency action was to preserve assets for the benefit of injured investors, and this resolution accomplishes that goal.” It is, in my experience, a rare occasion in which the SEC so expressly acknowledges that separate private securities litigation has sufficiently fulfilled the agency’s objectives in seeking to compensate injured investors.

There are a number of aspects of the circumstances involved here that are work considering in connection with the more recent wave of SPAC-related securities class action litigation. That is, by my count, there have been 26 SPAC-related securities class action lawsuits filed in 2021 alone. The Akazoo securities suit, as well as the SEC’s enforcement action, were both filed in 2020, and so the Akazoo suit is not reflected in the tally of 2021 actions. However, though the Akazoo suit relates to an earlier time period, some of the allegations in the case are similar to many of the allegations in the more recently filed actions. For example, both the private securities suit against Akazoo and the SEC enforcement action related to a collapse in the company’s share price following publication of a short-seller report raising questions about the company’s operations and finances. As I noted in a recent post (here), ten of the 26 SPAC-related securities suits involving companies whose share prices declined following publication of short-seller reports. In addition, another of the SPAC-related securities suits filed in 2020, the high-profile lawsuit against Nikola, also contain allegations of a decline in the company’s shares following the publication of a short-seller report. Clearly, it is not just the SEC that is focusing on SPAC-related transactions; short-sellers are as well.

But the most important point about this enforcement action and the settlement is that the liability risks that SPAC transactions and SPAC-related cases include not only the possibility of private securities class action litigation, but also the possibility of SEC enforcement action. The ultimate outcome of the action also reinforces the observation that the risk of litigation and enforcement activity can result in significant costs and recoveries. The fact that Akazoo had to fight parallel private securities litigation and SEC enforcement action also has defense cost implications that could be important for post-SPAC-transaction companies will want to take into account when assessing the adequacy of their D&O insurance limits.

In connection with the magnitude of this settlement, it is worth recalling, as I noted in my post about the prior Akazoo securities class action settlement, that the securities suit settlement was only a partial settlement, as the insurer’s on Akazoo’s post-merger go-forward D&O insurance program, as well as certain other parties, did not participate in the settlement. The $35 million settlement was funded in part by a cash payment from Akazoo itself, and a $9 million payment by MMAC’s D&O insurer. Depending on the outcome of the ongoing Akazoo private securities litigation (and perhaps attendant insurance coverage litigation), the ultimate aggregate cost of resolving the Akazoo litigation could prove to be more than $35 million.

One final note. The sequence of litigation events relating to Akazoo involved first a securities class action lawsuit and then a subsequently filed SEC enforcement action. The recent events relating to Stable Road Acquisition Corporation, which was recently hit with an SEC enforcement action (as discussed here), was that first the SEC filed its enforcement action, and then plaintiff’s attorneys filed a separate private securities class action lawsuit based on the same allegations. The point here is that the private securities litigation and SEC enforcement activity is not mutually exclusive – as in fact the settlement of the Akazoo enforcement action discussed above underscores.

SEC Enters Settlement in SPAC-Related Enforcement Action Against Akazoo published first on http://simonconsultancypage.tumblr.com/

The Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster  Here’s a picture of our panel, following the session. From left to right, Darren Pain of The Geneva Association (moderator); Neal Beresford, Clyde & Co; John Pilkington, Ascot Syndicate; me; and Andrew Hornsblow, Dale Underwriting Partners

Here’s a picture of our panel, following the session. From left to right, Darren Pain of The Geneva Association (moderator); Neal Beresford, Clyde & Co; John Pilkington, Ascot Syndicate; me; and Andrew Hornsblow, Dale Underwriting Partners  It was a particularly special part of my visit to Lloyd’s in connection with the conference to be invited to dinner in the famous Adam Room, an enduring vestige of venerable Lloyd’s traditions in the present-day ultra-modern building.

It was a particularly special part of my visit to Lloyd’s in connection with the conference to be invited to dinner in the famous Adam Room, an enduring vestige of venerable Lloyd’s traditions in the present-day ultra-modern building. The dome of St. Paul’s viewed from the 11th Floor of the Lloyd’s Building

The dome of St. Paul’s viewed from the 11th Floor of the Lloyd’s Building  It was a beautiful Sunday morning for a walk in Hyde Park on my first full day in London

It was a beautiful Sunday morning for a walk in Hyde Park on my first full day in London  After the walk, it was time for a traditional Sunday Roast at a pub on Old Brompton Road. Roast chicken in gravy, roast root vegetables (carrots, turnips, and parsnips), with a Yorkshire Pudding filled with sausages, and a little side salad.

After the walk, it was time for a traditional Sunday Roast at a pub on Old Brompton Road. Roast chicken in gravy, roast root vegetables (carrots, turnips, and parsnips), with a Yorkshire Pudding filled with sausages, and a little side salad. After lunch it was time for an afternoon concert at Cadogan Hall in Sloane Square. It was such a nice afternoon outside it was hard to go indoors.

After lunch it was time for an afternoon concert at Cadogan Hall in Sloane Square. It was such a nice afternoon outside it was hard to go indoors.  It was beautiful indoors as well. Cadogan Hall is such a great music venue. The concert was a performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto. The concert was part of what had been planned as a series of five concerts of Beethoven’s five piano concertos, with Elizabeth Sombart at the piano, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. I attended the first concert in the series in November 2019, the last time I was in London. However, due to the coronavirus outbreak, the second, third, and fourth concerts in the series were cancelled. The fifth concert was rescheduled to a time that coincided to my recent visit and there was a certain symmetry to my being there.

It was beautiful indoors as well. Cadogan Hall is such a great music venue. The concert was a performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto. The concert was part of what had been planned as a series of five concerts of Beethoven’s five piano concertos, with Elizabeth Sombart at the piano, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. I attended the first concert in the series in November 2019, the last time I was in London. However, due to the coronavirus outbreak, the second, third, and fourth concerts in the series were cancelled. The fifth concert was rescheduled to a time that coincided to my recent visit and there was a certain symmetry to my being there.  Richmond Green, a roughly 12 acre open space at the center of the town of Richmond. A very pleasant place on a fall afternoon. Legend has it that in the Middle Ages jousting tournaments took place on Richmond Green.

Richmond Green, a roughly 12 acre open space at the center of the town of Richmond. A very pleasant place on a fall afternoon. Legend has it that in the Middle Ages jousting tournaments took place on Richmond Green.  A view of the Thames River looking west from Richmond Bridge

A view of the Thames River looking west from Richmond Bridge The riverside at Hammersmith, viewed from the south shore. Note that the river is at low tide.

The riverside at Hammersmith, viewed from the south shore. Note that the river is at low tide.  Hammersmith Bridge at dusk

Hammersmith Bridge at dusk  Tate Britain exhibits British Art from the 15th to the 20th centuries. It has a particularly fine collection of paintings by J.M.W. Turner.

Tate Britain exhibits British Art from the 15th to the 20th centuries. It has a particularly fine collection of paintings by J.M.W. Turner.  The Imperial War Museum. I never made time in prior trips to visit, but I now see that that was a mistake. It is an excellent museum, with designed displays highlighting interesting historical artifacts. The new WWII exhibit is particularly well done.

The Imperial War Museum. I never made time in prior trips to visit, but I now see that that was a mistake. It is an excellent museum, with designed displays highlighting interesting historical artifacts. The new WWII exhibit is particularly well done.  Fortnum & Mason, the Royal Grocer, on Piccadilly. During my visit there, I stocked up on indispensables such as tea, coffee, and chocolate.

Fortnum & Mason, the Royal Grocer, on Piccadilly. During my visit there, I stocked up on indispensables such as tea, coffee, and chocolate.  Just a few steps east of Fortnum & Mason on Piccadilly is Hatchard’s, the oldest book store in London. I spent the afternoon in the History Books section and came away with an armful of books (I brought a separate carry bag with me to London in anticipation of the need to transport books back home).

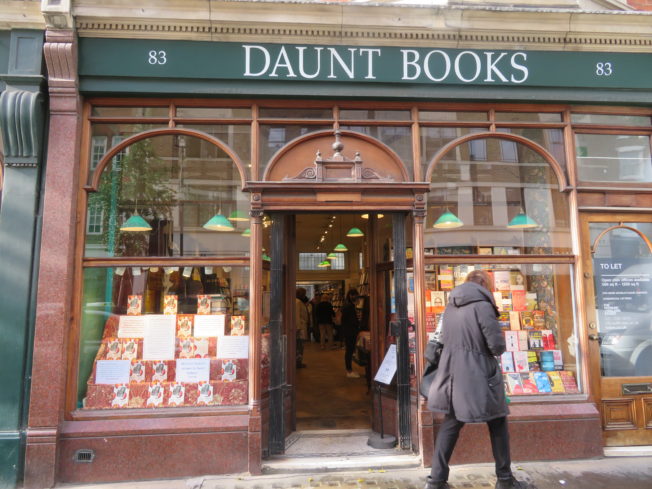

Just a few steps east of Fortnum & Mason on Piccadilly is Hatchard’s, the oldest book store in London. I spent the afternoon in the History Books section and came away with an armful of books (I brought a separate carry bag with me to London in anticipation of the need to transport books back home). Another famous London bookstore, Daunt Books, on Marylebone High Street. The store has an eccentric organization; it groups the books by country (with fiction and nonfiction arranged together). It as an interesting place with a lot of interesting books, in an interesting arrangement.

Another famous London bookstore, Daunt Books, on Marylebone High Street. The store has an eccentric organization; it groups the books by country (with fiction and nonfiction arranged together). It as an interesting place with a lot of interesting books, in an interesting arrangement.  The original Twinings tea, on The Strand (directly across the street from the Royal Courts of Justice). It was Britain’s first tea room when Thomas Twining opened it in 1706, and it as been operating on the site ever since.

The original Twinings tea, on The Strand (directly across the street from the Royal Courts of Justice). It was Britain’s first tea room when Thomas Twining opened it in 1706, and it as been operating on the site ever since.  Almost none of the marchers were wearing masks – and what could go wrong with tens of thousands of unvaccinated and unmasked marchers chanting, singing, and shouting? I kept my distance…

Almost none of the marchers were wearing masks – and what could go wrong with tens of thousands of unvaccinated and unmasked marchers chanting, singing, and shouting? I kept my distance…  Green Park, the viridescent heart of London. My favorite place. It was good to be back.

Green Park, the viridescent heart of London. My favorite place. It was good to be back.  A Canadian-based deep-sea mining company is the latest firm to be hit with a SPAC-related securities class action lawsuit. The company, which plans to mine the seabed for materials to be used in electric vehicles batteries, merged with a SPAC in September 2021. The company’s share price recently declined following news reports and a short-seller report questioning the company’s financing, licensing, and its claimed sustainability credentials. A copy of the October 28, 2021 complaint can be found

A Canadian-based deep-sea mining company is the latest firm to be hit with a SPAC-related securities class action lawsuit. The company, which plans to mine the seabed for materials to be used in electric vehicles batteries, merged with a SPAC in September 2021. The company’s share price recently declined following news reports and a short-seller report questioning the company’s financing, licensing, and its claimed sustainability credentials. A copy of the October 28, 2021 complaint can be found  In a

In a  I have always felt an aversion to the works of Richard Wagner; his massive and melodramatic style, his well-known antisemitism, and the association of many of his operas with Nazi culture, have always seemed reasons enough to avoid his music. It was with some surprise then that, after hearing a fascinating radio interview of The New Yorker’s music critic

I have always felt an aversion to the works of Richard Wagner; his massive and melodramatic style, his well-known antisemitism, and the association of many of his operas with Nazi culture, have always seemed reasons enough to avoid his music. It was with some surprise then that, after hearing a fascinating radio interview of The New Yorker’s music critic